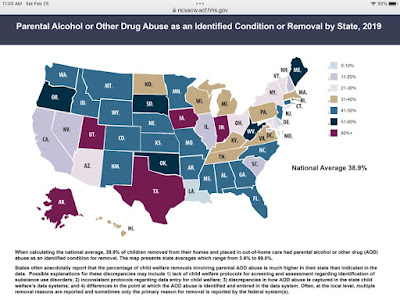

“Thirty-nine per cent of children enter foster care because of parental drug use” is the most commonly quoted statistic regarding the role of drugs in a child’s removal from home. However, that number is an average of US state removal statistics. While recently updating my book Will I Ever See Your Again? Attachment challenges for Foster Children, I came across the following graph indicating that the proportion of children who enter foster care due to parental drug use varies greatly from state to state from 3.6% to 69%. (Source: AFCARS 2019, most recent data.)

insidefostercare.com

Parental Drug Use as the Condition for Removal

Changes to AZ Law Help Foster Children “Stay Put...”

I have served on the Arizona Foster Review Board for 21 years. A few years ago we had a case in which a mother and her 3-year old daughter, Kiley, moved to Arizona from Ohio after the mother’s divorce from Kiley’s father. Although he knew the location of the mother and his daughter, the father made no effort to keep in contact with them. The mother remarried but when Kiley as 4 1/2, she was removed from the mother and step-father and placed in foster care due to domestic violence and other issues. The mother’s parental rights were terminated and Kiley was placed with a foster-adopt family to which she quickly became bonded. Almost three years later, when Kiley was 7, the DCS case worker located Kiley’s father in Ohio in an effort to place Kiley with him. Kiley did not remember her father; she thought that her step-father was her ‘real’ father. When asked in an interview about his daughter’s activities and likes and dislikes, Kiley’s biological father knew nothing about her. He also refused to acknowledge that Kiley had suffered any trauma from the violent environment from which she was removed. Kiley, on the other hand, named her foster mother, “Mommy Cindy” and her foster father, brothers, and sister when asked who was in her family. The psychologist who was contacted to perform a bonding assessment described the only in-person visit between Kiley and her biological father as having “gone poorly.” Conversely, when he observed Kiley with her foster mother, he reported that “their interaction was seamless.” The psychologist concluded that the “prognosis that the father will be able to demonstrate minimally adequate parenting is poor” and that there was a “potential traumatic emotional cost” of moving Kiley to her father in Ohio based on Kiley’s “lack of attachment and relationship with her father.” An additional concern was that the father also had 6 other children with four women and a drug arrest background. Despite the psychologist’s recommendations, the case plan of adoption, Kiley’s 3 years with her future adoptive family, and fierce objections from the foster parents as well as sadness and despair from Kiley, herself, she was moved to her father in Ohio.

This story is not uncommon. Sometimes, years after a child is placed in a foster/adopt home with adoption processes well underway, a relative is found or “pops up” and the child is moved from what may have been the only loving home the child has ever known, to be placed with “family” who do not know her at all, handing the child another traumatic event on top of the one that brought the child into foster care in the first place.

Another recent case involved a substance exposed newborn placed in a foster-adopt home shortly after birth. The foster mother drove from the family’s rural home over 150 miles to Phoenix Children’s Hospital weekly to attend to the child’s drug-exposure-caused withdrawal symptoms, eating difficulties, and developmental disabilities for 15 months (a time span that surely encompasses the period during which the child formed an attachment to the foster mother) until a great aunt and uncle from another state appeared and was awarded custody of the child by the judge. The great aunt and uncle did not know the baby or the baby’s many problems. I testified as an expert witness in that case that moving the child away would be traumatic for the child on many levels. I was beyond shocked at the court’s decision to move the child.

Fortunately, Arizona lawmakers addressed these problems in August of 2018 through modifications to Arizona Revised Statutes, Title 8 - changes that would have changed the outcome in both of these scenarios.

For Kiley, modifications to ARS 5-514.03(A) addressing kinship care would have given her a better chance of remaining with the family that she loved by replacing “the program shall promote the placement of the child with the child’s relative for kinship foster care” with “the placement of the child who is in the custody of the department shall be determined by the best interests of the child (emphasis added.) Kiley’s best interest would have been to remain with her potential adoptive home which had been providing a loving home for almost 3 years.

For the infant in the second scenario, kin who appear 15 months after a foster adopt placement would not be considered for placement because of this added time limit: “The department shall use due diligence in an initial search to identify and notify adult relatives of the child or person with significant relationship with the child within 30 days after the child is taken into temporary custody.” (Emphasis added.)

An added time limit to find a permanent home for infants in care would also have prevented the child’s move to a great aunt and uncle she did not know:

ARS 8-503(A)(10): (The department) shall “maintain a goal that infants who are taken into custody by the department be placed in a prospective permanent placement within one year after the filing of a dependency petition.

Also, ARS 8-514(B)3 gives some foster parents equality with kin: “A foster parent or kinship caregiver with whom a child under three years of age has resided for nine months or more is presumed to be a person who has a significant relationship with the child.”

The infant had been with the potential adoptive home that provided extraordinary care for serious effects of drug exposure for over 15 months giving the foster parents equality with kin. She was exactly where she should have stayed.

The Role of Culture in Child Dependency Cases

Cultural

Connections for Foster Children

Last year I was

asked to develop a training for the Arizona Court Improvement Program to

address the role of culture in child dependency cases. As I prepared the

presentation, I wasn't sure where to begin to address the question, "what is role of culture in

child dependency cases? From my FCRB experience, I know that Section III

(D) in the DCS Progress Report addresses “efforts to

maintain cultural connections, including opportunities for the child to build

cultural awareness, identity, and involvement.”

From a long list

of definitions of “culture,” I selected, “society’s common foundation of

beliefs and behaviors and its concepts of how people should conduct

themselves” (Hunter School of Social Work web page.) I then began putting together

the presentation with the idea of addressing national and ethnic cultural

differences and how we assure that the child’s cultural “beliefs, behaviors,

and concepts” remain in the child’s life as he moves through the foster care

system. Pretty straight forward.

But it quickly became

apparent that not every child is tied to an ethnic or national culture. My grandmother was born in

Prague, Bohemia, and came to the US as a child bringing her Bohemian (note the

capital “B”) ways with her. Her

daughter, my

mother, cooked Bohemian food, knitted “continental” style, spoke to her mother

in Bohemian. She had clearly adopted some of her mother’s culture. My brothers and I have some

curiosity about Bohemia (now Czech Republic) but no real connection to the

Bohemian culture.

So we make

efforts to assure that those children who are

tied to an ethnic or national culture keep those connections. But, I soon realized that cultural influence extends far beyond

just ethnic/national culture. Additional

cultural influences include the foster child’s family, neighborhood,

church/organizations, and school. Each of these “cultures” (aka

“microsystems”) have common beliefs and behaviors and a child placed in foster

care loses connections to all of them in one swift move. As a foster

child, I clearly remember the experience of being placed into different foster

homes. It was almost paralyzing. And it didn’t matter whether

it was kinship or non-kinship placement, or if the foster parents and their

home were perfect in every way; the rules were different from my home “culture” and I didn’t know what

they were. In one “kinship” placement, my brother and I went to a

new school for three weeks. We were lost

in that particular school culture. Nothing was the same; not the

school work, the teaching methods, the rules, and no one answered our main question,

“how come no one is wearing their uniforms?” (We were Catholic school kids and

that was true “culture shock.”). We were also far away from

our church where we were both involved with Scout troops and, of course, we did

not know our new neighbors (church and neighborhood - two more cultures lost.) But, for us, it was more of a

temporary stressor because we knew we would be reunited with our mother and older

brothers eventually.*

For children who

are abused/neglected, the “culture shock” is much worse. Children who have been

physically abused, or who have not had adequate food, managed to adapt to their

abusive environments for survival. Perhaps they learned how to

sneak and hide food or steal change to buy food; or they became adept at

sensing when it was safe to approach a parent and when it wasn’t. Most of these children have

spent their entire lives in abusive/neglectful homes. It’s all they know; and their

neural pathways for their specific survival behaviors are strong. When they are removed and

placed in foster care, they enter unfamiliar territory with unknown rules and

new people who might or might not hurt them. They are unsure of how to get

food; nervous about attending a new school, and have no neighborhood friends to

play with after school.

In their new placement, these children

may display behaviors that we would consider “survival” tactics in

their abusive homes but “odd” in their foster homes e.g., hoarding food,

stealing money, or raising their arms in self-defense when approached by an

adult. That was their home culture. At school they may be so far behind that they become lost

or just give up trying (every move through foster care results in 4-6 months

loss of academic progress in school.). Regardless of the quality of their

care, their removal from home and school cultures may be unsettling because the

abuse and neglect way of life is all they know.

It becomes

apparent that, in addition to assuring connections to ethnic/national cultures,

we also need to consider connections to the child’s “microsystems.” So we ask, always with the safety of the child in mind,

“Is it possible for the child to remain in the same school (in accordance with

ARS 15-816.01) and/or continue to participate in church/scouting

activities? Can we enlist the assistance of safe family members for

transportation to and from these locations to help keep the child’s connection

to friends and family strong? How can we

safely help the child preserve some connection to his extended family,

neighborhood, school, church, extracurricular activity? Children removed from

their homes will always have difficulty adjusting to a new environment, but the

more “cultural” connections we can maintain for them, the less “culturally shocking” their

move will be.

*We

were in foster care each time our mother, who was battling cancer, was

hospitalized, which was quite often, but we returned home when she did. We

returned to foster care after she died and eventually were placed with an aunt

and uncle. Our older brothers were self-sufficient